I've been wanting to write about the assumptions we inevitably make any time we encounter a new situation or a new person, but I didn't think I had a very compelling story. Just describing how easily some of my own assumptions about this project have been shattered seemed trite or self-serving. I wanted to wrestle with the idea that it sometimes seems to take something different to get us out of our comfort zones, so we can finally see with a new perspective.

I've been wanting to write about the assumptions we inevitably make any time we encounter a new situation or a new person, but I didn't think I had a very compelling story. Just describing how easily some of my own assumptions about this project have been shattered seemed trite or self-serving. I wanted to wrestle with the idea that it sometimes seems to take something different to get us out of our comfort zones, so we can finally see with a new perspective. I was thinking about behavioral traits -- assumptions, for example -- and how they originally stemmed from our primitive ancestors' needs to survive and succeed.

I was thinking about behavioral traits -- assumptions, for example -- and how they originally stemmed from our primitive ancestors' needs to survive and succeed.The ability to make an assessment of her environment in response to an experience probably helped my neanderthal ancestor find the foods that were nutritious and avoid hazards like sinkholes and crevasses. The better she could discern friend from foe and safe plant from toxic, the more chance her genes had to pass on to the next generation.

Genetic evolution is very slow, occurring over millions of years with an occasional accidental spurt. By contrast, the evolution of our society moves quickly -- perhaps at a break-neck pace.

Genetic evolution is very slow, occurring over millions of years with an occasional accidental spurt. By contrast, the evolution of our society moves quickly -- perhaps at a break-neck pace.The way we talk, how we organize ourselves in groups, the approaches we make to decisions, what political parties we belong to and so forth, are plastic and can change many times within a single generation. (Because these changes occur so quickly scientists might even wonder what elements of social behavior have primitive importance or influence the behavior of subsequent generations.)

In any case, the fact that we can make assumptions in the face of an event has a strong genetic basis. What I'm interested in is the fact that we can change our assumptions. So often it is in response to an interesting experience. But do we require such an experience to get us out of our comfort zone, or can we imagine a new perspective much like a good chess player works out several moves in advance?

In any case, the fact that we can make assumptions in the face of an event has a strong genetic basis. What I'm interested in is the fact that we can change our assumptions. So often it is in response to an interesting experience. But do we require such an experience to get us out of our comfort zone, or can we imagine a new perspective much like a good chess player works out several moves in advance?This must be part of the creative process. But how to think from different perspectives? This I leave for you to decide.

It's a good thing that assumptions can be changed. If my assumption was that a person who was blind could not see, I would be wrong. That assumption wouldn't change my own fate, but it would certainly hinder the progress of our society as a whole.

It's a good thing that assumptions can be changed. If my assumption was that a person who was blind could not see, I would be wrong. That assumption wouldn't change my own fate, but it would certainly hinder the progress of our society as a whole.

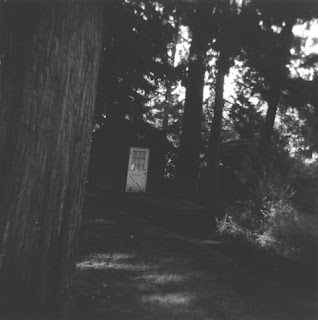

With limited time, I also elected not to print on archival quality paper. I instead used RC paper, the thickly-coated, not-so-attractive resinous paper used more for speed of processing.

With limited time, I also elected not to print on archival quality paper. I instead used RC paper, the thickly-coated, not-so-attractive resinous paper used more for speed of processing.

The black and white film we used for the Holga, a 120 sized film, comes on a plastic spool about 2" wide. I decided to use Kodak for this project; not only is it less expensive than other brands, the film itself feels thicker and has more friction, making it a little easier both to load into the camera and also load onto a developing reel. We used standard 400 speed film, which is pretty good for covering most lighting situations, and has the advantage of being compatible with the chemical processes used in the college darkroom lab.

The black and white film we used for the Holga, a 120 sized film, comes on a plastic spool about 2" wide. I decided to use Kodak for this project; not only is it less expensive than other brands, the film itself feels thicker and has more friction, making it a little easier both to load into the camera and also load onto a developing reel. We used standard 400 speed film, which is pretty good for covering most lighting situations, and has the advantage of being compatible with the chemical processes used in the college darkroom lab.