The black and white film we used for the Holga, a 120 sized film, comes on a plastic spool about 2" wide. I decided to use Kodak for this project; not only is it less expensive than other brands, the film itself feels thicker and has more friction, making it a little easier both to load into the camera and also load onto a developing reel. We used standard 400 speed film, which is pretty good for covering most lighting situations, and has the advantage of being compatible with the chemical processes used in the college darkroom lab.

With film in the camera, any time the shutter is opened, light will enter the camera and expose the film lying against the inside of the camera back. This image is about 2" wide (the approximate width of the film) by 2" high. The film is manufactured to hold 12 such images, but there are things one can do to vary this. Rolling film only partway, for example, will single-expose a 2" swatch and double-expose a swatch matching how far one rolled the film. You can shoot entire rolls like this; they come out looking a little "artistic", as the exposure is different across the real estate of the film, but I've had some really good results with this method and enjoy shooting this way.

Since Holgas are cheap, people modify them to hold 35mm film (exposing a bigger swatch of the film than one normally is used to), or two rolls of 35mm film one above the other. Or you can shoot a roll of 35mm on the lower half of the roll and then re-shoot it on the upper half of the roll. The possibilities for really wild uses of film are endless.

For 120 film, a plastic frame can be clipped into the camera, allowing you to expose less than the 2" wide swatch.

In my opinion, the best use of 120 film is the square exposure that is approximately 2" by 2" (or 6 x 6 centimeters, as 120 implies). I find these proportions very graceful. The negative is large and the image crisp (one hopes). It is far easier to work with a grain focuser and I am generally enlarging to a lesser degree than I would enlarge a 35mm negative. When printing onto, say, 8 x 10" paper the image occupies a nice position with landscape orientation. The balance created by the white margin gives a pleasant weight.

With a Holga, the image is captured so that the floor or horizon of the subject runs parallel to the edge of the film. This makes handling of the negatives straightforward; they face you directly when you lay them out in negative sleeves or in a negative carrier for the enlarger. I mention this because my Mamiya C3 (an old-fashioned portrait photographer's twin lens camera) and other such cameras capture the subject with the floor or horizon of the image running perpendicular to the edge of the film. Since the image faces run lengthwise, this makes for more steps in handling them when working with them. So there was yet another reason for using the Holga with 120 film.

When shooting with 120 film, it rolls off of its plastic spool and onto another spool. When done shooting, you remove both the film (rolled onto the takeup spool) and the original but now empty film spool. You can recycle the original spool over to become the take-up spool for the next roll of film.

The film is removed from the camera without letting it spring open to expose everything you took all that time to photograph. There are fiddly bits of paper the size of a cigar band you can moisten and wrap around the roll to hold it secure. I usually put the film into a piece of aluminum foil for security. I might store it in the refrigerator if I can't develop it right away.

The next step is done in the dark, ideally in a film-loading cubicle, which is a light-tight closet except for the barest bit of light one can discern peeking beneath the door. I always lean way over the work table in the closet. In case I drop the film, it hopefully will not fall onto the floor and risk becoming exposed. To develop the film, you release and unwind the roll, separating the film from its backing paper. The bit of tape that held the two together can be folded over the edge of the film. Then the film is inserted into and rolled onto a plastic reel in such a manner that none of the photographic surfaces touch each other. You can imagine an old movie projector, with film rolling from spool to spool. Imagine the spools being made such that there is space between the film surfaces as the film rolls onto the spool. In this way, the 120 film spool can be placed into a developing tank, and with the right agitation during development, all of the film will receive appropriate contact with the developing media.

Another reason for using Kodak film is the size of the film. Because the exposed surface is larger, to me it presents a larger accident waiting to happen. With a more delicate film I worry about introducing wrinkles into the film as I load it onto the developing reel, and about scratching the film. The film is vulnerable in the developing tank when I am agitating the chemicals across the surface, even so, I try to agitate gently. Lastly, other films I've tried require a longer developing time, and over the life of a project this can add to a significant increase in time.

There is a critical time when the film is hanging to dry and it is vulnerable to scratches and to dust. This can be the bane of working with film in a shared or academic environment. On more than one occasion I've come upon a student -- so captivated by an image -- leaning into the drying racks, eagerly flicking the protective curtain this way and that, and more than likely dusting everyone's negatives with fine particles from the curtain (which is intended to be a dust magnet.)

This first batch that Susan shot included 5 rolls of film. For safety's sake, I developed these in three separate batches, each taking a little over an hour. I then hung the negatives to dry for about an hour and a half each.

When the negatives were dry, I cut them into segments to fit into clear plastic negative sleeves. Each roll fits on a page of negative sleeves approximately 3 frames across in four rows of frames.

I had just enough time the first day to print contact sheets for three of the rolls. The remaining two rolls had to wait until the next day I was in the darkroom.

Texture became extremely important to me as I lost my sight. I'm sure sighted people relate to texture in their own way, but to me texture is a very sensual thing. Touch is how I explore what things are; the richer the textures the better. Textures create for me interesting patterns. I love adjoining them with one another to complete a tapestry of sorts where nature is concerned especially. I am sure that textures must be pleasing visually but touching the textures is far more enjoyable I think.

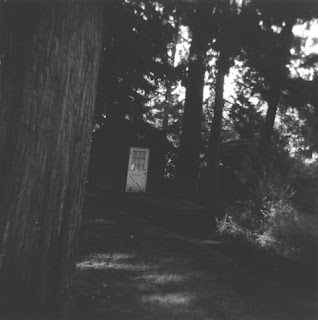

Texture became extremely important to me as I lost my sight. I'm sure sighted people relate to texture in their own way, but to me texture is a very sensual thing. Touch is how I explore what things are; the richer the textures the better. Textures create for me interesting patterns. I love adjoining them with one another to complete a tapestry of sorts where nature is concerned especially. I am sure that textures must be pleasing visually but touching the textures is far more enjoyable I think. So, too, in nature one can develop an eye or "feel" for what texture can do for a photo. Gardens lend themselves well to these kind of rich shots. Some I have taken of different kinds of flowers, some in pots surrounded by spikey iris by a stump next to a clearing with gravel and an old craggy fence have been great texture-filled photos which lent themselves well to black and white stills. At least they were fun to shoot and fun to take as I felt where to point the camera!

So, too, in nature one can develop an eye or "feel" for what texture can do for a photo. Gardens lend themselves well to these kind of rich shots. Some I have taken of different kinds of flowers, some in pots surrounded by spikey iris by a stump next to a clearing with gravel and an old craggy fence have been great texture-filled photos which lent themselves well to black and white stills. At least they were fun to shoot and fun to take as I felt where to point the camera!

The black and white film we used for the Holga, a 120 sized film, comes on a plastic spool about 2" wide. I decided to use Kodak for this project; not only is it less expensive than other brands, the film itself feels thicker and has more friction, making it a little easier both to load into the camera and also load onto a developing reel. We used standard 400 speed film, which is pretty good for covering most lighting situations, and has the advantage of being compatible with the chemical processes used in the college darkroom lab.

The black and white film we used for the Holga, a 120 sized film, comes on a plastic spool about 2" wide. I decided to use Kodak for this project; not only is it less expensive than other brands, the film itself feels thicker and has more friction, making it a little easier both to load into the camera and also load onto a developing reel. We used standard 400 speed film, which is pretty good for covering most lighting situations, and has the advantage of being compatible with the chemical processes used in the college darkroom lab.